Views: 13 Author: Staff Publish Time: 2019-10-07 Origin: Electronics Weekly.com

To achieve the best connection for your specific application, the primary consideration is the board or mounting configuration. The orientation or mounting of the connection, whether parallel, 90 degree or vertical, must subsequently be taken into account.

For signal connectors, the ideal solution would be to specify 360 degree shielding around the signal. While this is the optimum, there is a severe cost penalty attached.

Under certain circumstances, more specific EMI shielding or RFI shielding may be sufficient. Thinking outside the box, it may be desirable to keep the noise within the confines of the enclosure. This is true particularly for I/O connectors, which can act like antennas.

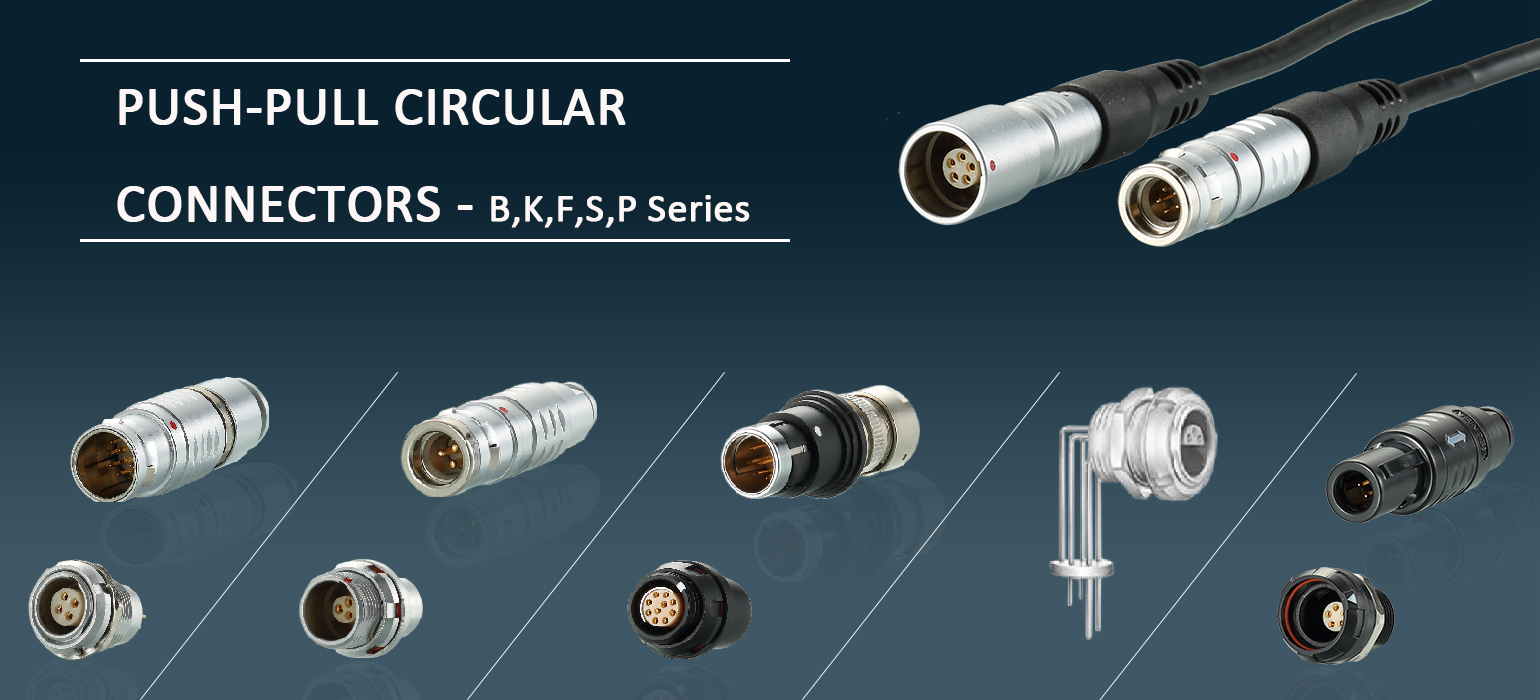

Conventional connectors typically have a positive latching feature to ensure that a given connector system will not easily unmate. However, backplane connectors are blind-mating and therefore do not, and should not, have positive latches. For I/O connectors a push-pull mechanism is often used. This is usually complemented by a screw coupling or bayonet locking mechanism. The most primitive form of connector mating is a friction lock. Although this solution is very economical, it is only viable for low pin counts – between 200-400g per contact requires a force of 2G – high pins counts will have no chance of disconnecting.

For the untrained technician unintentional polarisation can be an issue. For rectangular connectors, the RJ-45 being a good example, this occurs mainly in hot-pluggable mating applications, where the wrong pins or wrong wires are connected. There are easy ways of avoiding erroneous mating. One such method is to implement a coding scheme – a simple but practical approach to distinguishing the mechanical differences.

Hot plugging is a very interesting subject; there are two trains of thought here, first mate/last break or last mate and first break, both relying on either a longer pin or a socket closer to the pin. These mechanisms are often used in datacoms and telecoms applications, which regularly integrate redundant systems – so, if one card fails, an alarm is set off but the system doesn’t fail.

If we revisit the size versus number of pins trade-off, we need to ascertain the number of signals and the type of connector. First of all determine whether the signal is single-ended and differential: as a guideline all signals at 100Mbit/s and below are single-ended and above 1Gbit/s are differential.

The range between 100Mbit/s and 1Gbit/s is somewhat blurred and largely depends on the standards available; here you need to know the data rate and more importantly the rise time. For example, VME has a low rise time so there’s less noise into the connector. If there is impedance within the connector, there are reflections and this causes crosstalk. However, there are other causes of crosstalk.

Magnetic crosstalk can be avoided by using shielding. The best way of shielding a set of pins is by using a metal sheet or, as alternative, creating a pin field where every second or second pair of pins run to ground. A typical example would be backplane connectors with broadside coupled pairs, with the electrical signal in between the two traces. Press-fit connectors are ideal as they are relatively short, changing from differential pair inside to an electrical wave.

Going back to the number of signals, you need to ask: How many high-speed signals? What type? What control? Type of power? For example, if you want a connector with four differential pairs, six control signals and a 5A supply, you could consider sacrificing the grounds.

To overcome the electrical problems often associated with brass, phosphor bronze, beryllium copper, and other copper-based alloys, terminals are often plated with gold, tin and tin-based alloys, and palladium/nickel alloys. In addition, gold flashing is sometimes used to protect the contacts during storage which is subsequently stripped off at first contact.

System engineers must also consider the contact resistance against the required number of mating cycles. Tin, for example, has a contact resistance of 50mohm, which is not good but good enough for applications requiring only 20 to 50 mating cycles. If inside a box this is sufficient but in rack and panel applications where the card may need to be replaced, 50 mating cycles is too low.

Consider how the connector is to be terminated. DIP soldering is a common process for straight or 90 degree contacts. There is also wave soldering, however there is one drawback, a pure tin wave solder bath is very difficult to maintain. The pin in paste process is becoming more popular, but probably the best process is surface mount technology since there are no holes to cause failures and it is more cost-effective.